Back in the early seventies, while I was a student at the University of Houston, the local newspaper ran a joke front page on April Fools’ Day. Set fifty years into the future, the headline was “Two Cyborgs Killed in Laser Car Crash on Soon-to-be-Completed Gulf Freeway.”

The joke wasn’t about cyborgs or laser cars, but about the idea that the Gulf Freeway Project, begun in 1952, would still be under construction in the 21st Century. Sadly, that bogus newspaper story was printed more than fifty years ago and the freeway project is still under construction.

I was reminded of that old newspaper story as I drove between Las Cruces and El Paso yesterday. Though the two cities are only about fifty miles apart, the trip took considerably longer than it should have because twenty miles of Interstate 10 was still under construction. When the highway was last modernized, it desperately needed three lanes per side and they built only two, so now it needs four and they are only building three. Long before they finish the three, there will be cyborgs driving laser cars.

It was the middle of the afternoon, and if there was anyone working along that long stretch, I missed them. None of the heavy machinery was moving and the whole site looked shut down.

Highways can be completed much faster: half a century ago, between Puebla and Mexico City, I saw more than a half mile of highway constructed in a single week. I’ll grant you that it was flat land and the Mexican authorities were not hindered by such niceties as legal rights-of-way or environmental impact studies, but the highway was certainly finished.

Why do American highway jobs take so much longer to complete?

Delays result from multiple reasons. First, the projects are divided into multiple stages, frequently, with different contractors responsible for each stage. Ignoring the companies that plan and design the construction, there may be multiple companies responsible for relocating utilities (water, gas, electric, and fiber), for roadbed prep and drainage, for paving and surfacing, and for installing signage and barriers. If any of the companies responsible for any of these tasks is late, it creates a chain reaction of ever-increasing, subsequent delays.

Next is the problem of funding. State departments of transportation (like NMDOT and TxDOT) often don’t get all the money needed at once. Projects are split into fundable phases that may be spaced out over years. Politicians frequently divide the funding over years to lessen the “sticker shock” of the project cost. (Ever notice that politicians spread the cost or the income of a proposal over ten years? They assume you can’t do simple math.) Delays in federal or state budget cycles can push projects back months or years.

Getting all the required permits frequently delays projects, too. On just the fifty-mile trip I took yesterday, I crossed through two states, two counties, federal lands, and several small townships. The route passed through both areas of archaeological interest and endangered species zones. Even if a permit is acquired, special interest groups frequently challenge those permits in court, producing even more delays.

In addition, there is a nation-wide shortage of skilled highway construction workers. General construction workers can make $40K a year, with skilled heavy-construction workers bringing home three times as much. Along with a shortage of workers, there is a growing shortage of contracting companies bidding on the jobs.

The last two reasons for delays are a little unusual. First, there is a problem with safety barriers. I complained to my wife that the orange barrels were positioned such that they created very narrow lanes even though there was obviously nothing going on behind the barriers for at least twenty more feet. It turns out that if the barriers are only needed, for example, in phases 2 and 5 of a project, they leave them up for phases 3 and 4 to save money and to prevent driver confusion. The contractors are afraid that if they took down the barriers after the completion of Phase 2, you would ignore them when they went back up for Phase 5 ad thus endanger construction workers. This doesn’t actually delay construction, but the longer period of driving inconvenience makes us think it takes longer.

The last general cause of construction delay is the project bidding process. By law, the government must take the lowest bid. A contractor can save money by lengthening the construction project to the maximum time in order to shuffle construction crews and heavy machinery among multiple job sites and multiple projects. This approach keeps overhead low, maximizes equipment usage, and enables profit—even if the work proceeds slowly.

The contractor wins the bid, even though his completion time is much longer than that of other competitive bids. Public projects that are put out to bid rarely penalize a bid on the basis of the time to complete a project.

However, this “lowest cost” does not take into consideration several factors. Businesses along the proposed route suffer financial losses from the loss of customers," resulting in lower sales and hiring fewer employees. The government then loses both sales taxes and income taxes. Many businesses—particularly restaurants—end up closing along construction routes because their customers avoid the inevitable delays caused by traveling through construction sites.

Nor is the added cost from delayed highway construction strictly financial. Highway workers are seventeen times more likely to die on the job than office workers are, with the vast majority of those deaths due to accidents involving motorists. A motorist traveling through a mile of road construction is four times more likely to be involved in a fatal accident than while making the same trip on a completed highway. What is the estimated cost of a human life?

When calculating the cost of highway construction, U.S. government agencies, particularly the Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), use a monetary value for a human life to assess safety measures and cost-benefit analyses. This value, known as the Value of a Statistical Life (VSL), represents the economic cost of preventing a fatality, not the intrinsic worth of an individual. Currently, that number is between $10 and $12 million. Needless to say, that pitifully low number is not factored into the cost of highway construction bids.

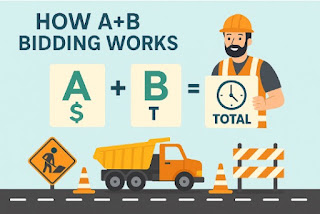

There is an alternative method of bidding that voters should insist our government use: it’s called A+B bidding. And no, it’s not a math quiz—it’s a way to keep bulldozers and construction workers from vanishing into thin air for six months at a time.

In the world of government construction contracts, “A” stands for the amount of money a contractor wants to be paid. That’s pretty standard—everyone wants the best deal, and the government usually picks the lowest bidder. But here's the twist: “B” stands for time—how many days the contractor says they'll take to finish the job. Each day has a price tag attached, called a "road user cost," representing the financial loss caused by traffic delays, detours, and donut spills.

So instead of just saying “Hey, we’ll do it for $4 million,” a contractor using A+B bidding says, “We’ll do it for $4 million in 100 days.” The government adds the money (A) and the time cost (B × daily delay cost), and whoever has the lowest total wins. This means a slightly more expensive bid that finishes faster will beat a slower, cheaper one.

A+B bidding flips the usual system by rewarding speed and efficiency, not just bargain-basement pricing. It’s good for taxpayers, great for commuters, and just might mean fewer orange cones decorating the freeway for years at a time. And fewer accidents.

There are a few other things that government could do to cut down the delays. Don’t award contracts until enough funding to finish the project has been allocated. Insist that contractors have bonds to ensure the cost of penalties imposed by delays. Pass legislation that allows businesses to sue contractors for business losses resulting from those delays. Currently, many government contracts explicitly waive consequential damages, limiting what can be claimed.

I could go on, but that is enough for you to think about the next time traffic is not moving and you have nothing to do but stare at the orange barrels and wonder why the cars in the other lane always move faster.

MY INTERNET NIGHTMARE ODYSSEY

ReplyDeleteThe information superhighway is under construction too!

https://virtualvillageorg.blogspot.com/2025/06/democrat-governors-internet-volcanoes.html

Forgot to sign. After 3 months I'm having to learn how to use my computer again.

ReplyDelete